It's So I Don't Kill Myself: Millennial Playwrights Seek Beauty in the Despair

Will Arbery's "Evanston Salt Costs Climbing," Bailey Williams's "Events" and Milo Cramer's "School Pictures" find wit and wonder, if not exactly hope

A few years ago, I worked in an office where the staff was mostly millennials, like myself. It was a typical chaotic start-up: open plan, fast-paced, long hours. One afternoon, a delivery arrived from Capsule for a co-worker. As she fished her medication out of the bag, a second co-worker noted that he also used Capsule for his meds.

“Oh, cool!” she smiled, then held up the package and declared brightly: “These are so I don’t kill myself!”

“No kidding,” he replied, even brighter. “Mine are so I don’t kill myself!”

This exchange kept replaying in my head this past month as I took in three bleakly comic, deeply brilliant new works, all by millennial playwrights: Evanston Salt Costs Climbing by Will Arbery (from The New Group), Events by Bailey Williams (from The Hearth), and School Pictures by Milo Cramer (at the Wilma Theater in Philadelphia). Each play mines humor and conjures an exciting theatrical language out of what could best be described as frantic millennial despair.

Evanston Salt Costs Climbing opens with two salt truck drivers preparing for a long shift on dark roads. “I want to kill myself,” Peter quickly announces to his baffled co-worker, Basil. He’ll say it again, many times. All the characters talk like this in Arbery’s bitter, caustic work. Their boss, Maiworm, deals with panic attacks. Her stepdaughter, Jane Jr., barely leaves the house, paralyzed by the hopeless state of the world.

Arbery’s whole play is suffused with a feeling of dread, a sense of something dark lurking underneath the characters’ feet, ready to swallow them up. We know this because Peter says it: “There’s something under everything and it’s making us all want to die.” Meanwhile Maiworm, racked with guilt over the dying world she is handing off to her stepdaughter, is fighting for a greener alternative to road salting–even if that means putting Peter and Basil out of a job.

In Bailey Williams’ Events, now at The Brick, a boutique design company descends into chaos in the days leading up to a high-stake event. The young staff, probably smart and talented, spends endless days struggling to spin sense out of owner Todd David’s nonsensical vision—a routine so ingrained that when David goes missing, they keep blindly working. Interspersed with these scenes are monologues from a mysterious figure called “Itchy,” who also worked in an office (maybe the same one, maybe not) and gradually realized a co-worker was poisoning her—though it is evident that Itchy herself is losing her grip on reality.

Finally in School Pictures, writer/performer Milo Cramer recalls five years as a private tutor in New York City preparing kids for the SHSAT, which determines admission to the city’s elite public high schools. On ukulele, toy piano, keyboard and more, the delightfully offbeat and very likable Cramer sings through musical snapshots of ten kids they tried to help. One such student is Javier, who refuses to do homework, citing the oncoming disaster of climate change. “Javier is 13 and thinks that he won’t live to be 30,” Cramer sings. “He says that all that’s left to do is party.”

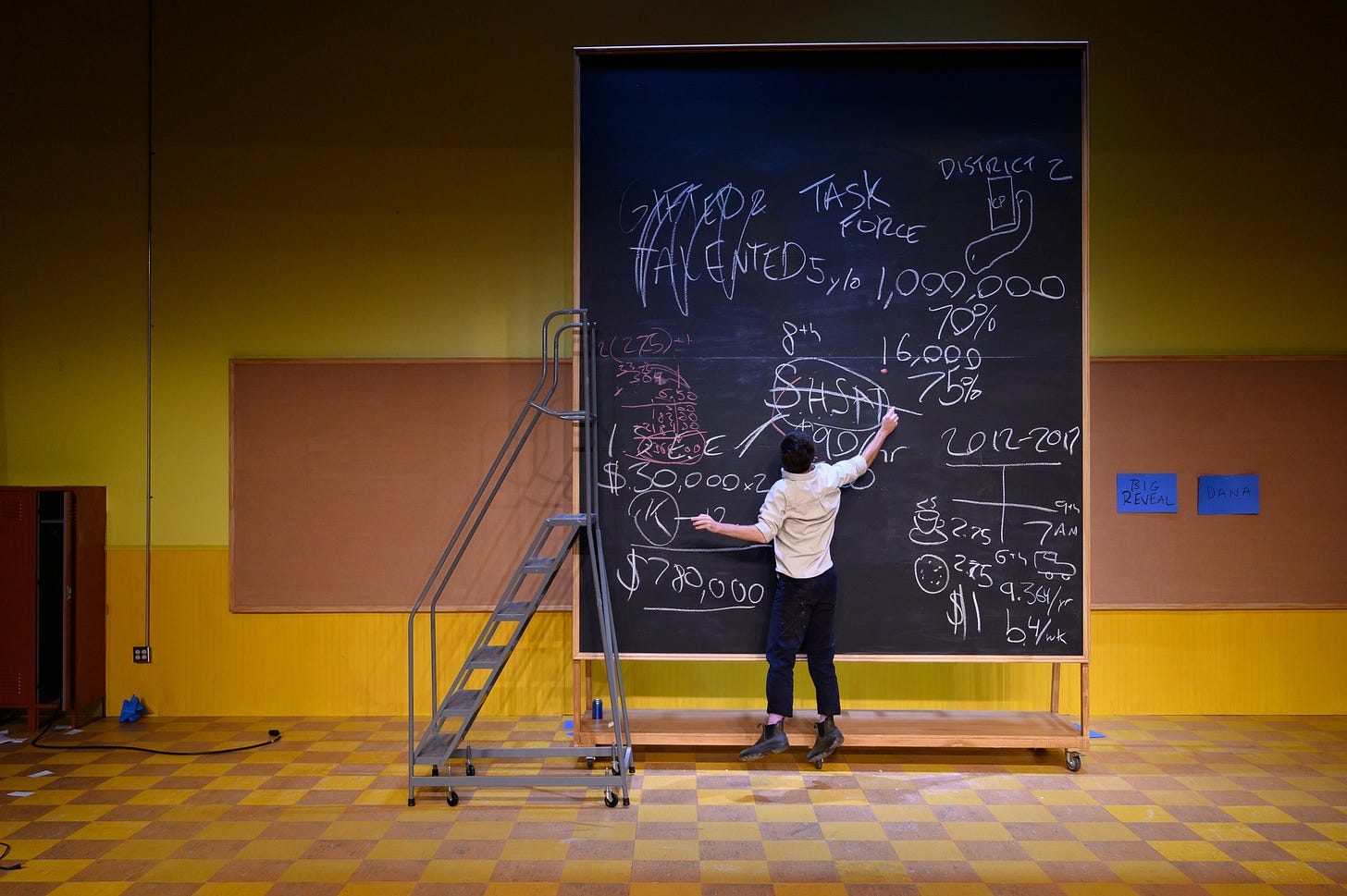

In the show’s final section, the theater becomes a classroom, and Cramer instructs the audience on New York City’s messed up gifted & talented testing structure, which has led to an increasingly segregated public school system. “I thought I was helping children,” Cramer concludes the mini-lecture. “I was really just a fucked-up cog, in a larger fucked-up system.”

That description fits all the characters in all three of these plays, which are not, any of them, the subtlest of texts. Evanston conjures the impending doom of climate change as a specter haunting the living as they struggle through this crumbling Earth (one literal such presence, a ghostly woman in a purple hat, makes multiple terrifying appearances). The workers of Events are forgetting how to even be empathetic humans as they let a toxic work culture take hold of their whole beings. School Pictures introduces us to ten strange, delightful children, then reminds us they’re stuck in a system that categorizes kids as ‘gifted’ or ‘normal’ in Kindergarten, with few off-ramps provided.

Yet our current moment is perhaps not one for subtlety anyway. Arbery, Williams and Cramer write how millennials talk, with the directness of a generation that has confronted disasters already with many more lurking on the horizon, meeting their doom with a grinning “fuck you” tossed into the darkness: “These are so I don’t kill myself!”

The broadness also, most crucially, allows for humor, since these artists, while not entirely unsentimental, have no interest in preaching. And so humanity’s predictable and repetitive failures are wittily theatricalized.

Evanston does this most literally, with an exhilarating time-jump sequence that leaps forward a year at a time, and sees Maiworm announcing her big plans for next year (“Well, not today”) over and over, and over, and over. With Events, Williams makes it hard to determine whether Itchy’s story is taking place before or after the play’s main storyline, suggesting an unending cycle of employees driven to their breaking point. And in School Pictures, Cramer’s closing class pinpoints the cyclical nature of political failures, as he details how New York has circled around the same education crises for years while effecting little change. But even that is funny—Cramer quizzes the audience on a math problem that stumps them, before finally revealing that questions exactly like this one appear on the SHSAT.

These three great pieces of theater have not uncovered these grand crises, but they theatricalize them with wit and empathy and find, even in the darkest of themes, a strange sort of beauty. Evanston isn’t about climate change; it’s about these characters losing the sure ground they once felt beneath their feet. The musical snapshots of School Pictures take on a tragic quality once Cramer has explicated the struggling system these strange, vibrant kids are fed into. Events isn’t about toxic work culture so much as about vibrant workers who have lost all sense of themselves.

In the final scene of Events, Itchy goes before an unidentified panel that is assessing her accusation of poisoning. The panel claims to be an outside third-party, but to our eyes, it’s the same staff we’ve been following through the show. Yet they are no longer individuals—now they speak as one, one blank, humorless voice that tells Itchy she is lying, that there is no poisoning, that everything is actually fine. It’s the saddest scene in any of these three plays. We can laugh at the darkness, or sing about it, or have our fun in spite of it—whatever we need to do. But to pretend it’s not there? That would really be tragic.